Editor's Choice

The Munby Papers

Sarah Hodgson

The Munby collection was bequeathed to Trinity College on the understanding that the deed boxes in which it was held were not to be opened until 1950. Shrouded in secrecy until that date researchers and scholars must have been elated to find the remarkable diaries of Arthur Joseph Munby contained inside. Those opening the boxes also found photograph albums, poetry and diaries written by Munby’s wife Hannah Cullwick.

|

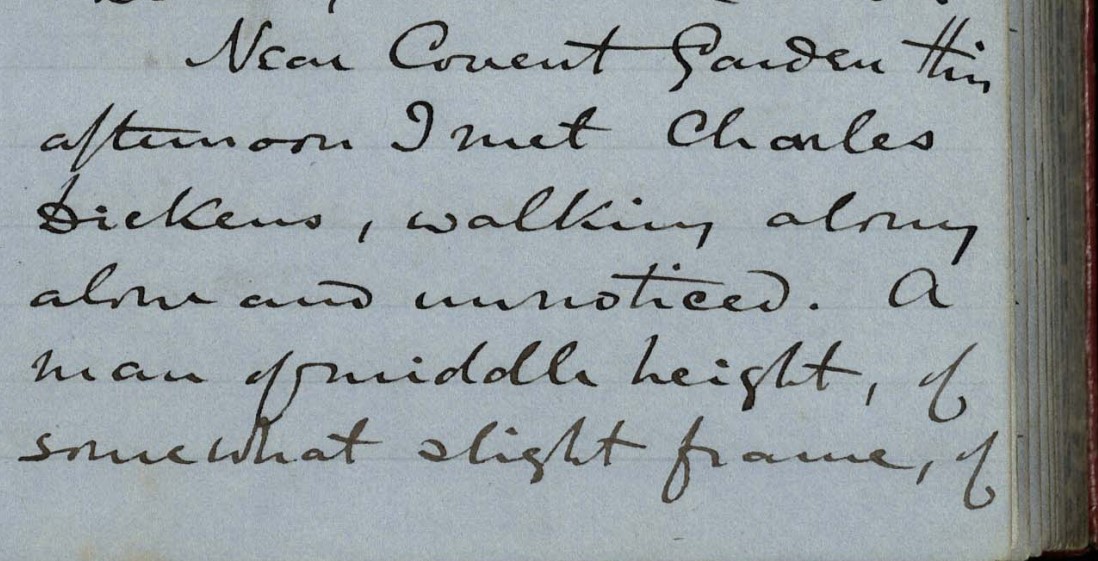

The Victorian era called for decorousness and virtuousness and Arthur Munby was a leading example of a proper Victorian gentleman. He was well educated, worked as a solicitor, a barrister and a civil servant, taught Latin and wrote and published poetry. He mixed in artistic and literary circles and several of his diary entries mention notable figures such as John Ruskin, William Makepeace Thackery and Charles Dickens. Yet Munby’s true passion and fascination lay with the observation of working women. Munby’s diaries are laden with rich descriptions of the daily toil, lives and emotions of these women he was so engrossed with.

|

|

Munby travelled all over Britain and Europe so he could meet women from different working backgrounds. His diary entries detail meetings with milkwomen, prostitutes, farm labourers, pea pickers, fisher girls, market women and many more. Munby writes about their appearance, daily tasks, wages and the power and education of modern English women in comparison to men. Particular attention is paid to his maid Hannah Cullwick who eventually became his wife. Their relationship was kept mostly secret for over nineteen years with Munby and Hannah even marrying in private. He writes of her often, including details of her daily cleaning routine, her appearance and, sadly, her accounts of violent abuse at the hands of previous employees. Interestingly, upon marrying Munby, Hannah’s role of maid within the household would not change.

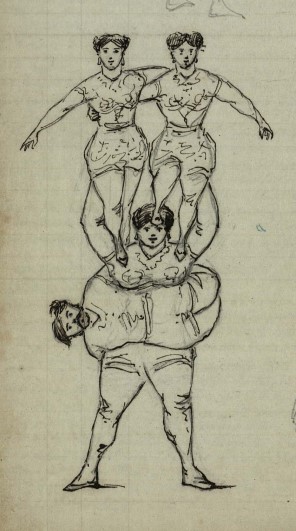

One of my favourite parts of these extraordinary diaries are the beautiful sketches of working women drawn by Munby which helps bring his written accounts to life. The documents are a treasure trove, even including sketches of female acrobats.

It is worth noting that Munby’s diaries are a dream for any researcher painstakingly making their way through manuscript documents; the neat writing, the meticulous attention to detail, the page numbers and the indexes! And that is before the reader even reaches the wonderful content which allows us to start understanding the lives of the hard working, brave and tenacious women in mid-century Victorian England. However one may view Munby and his fascination, the diaries are an invaluable source for scholars studying Victorian Britain, gender history and women’s studies.

This extraordinary collection is enhanced here with Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) technology to enable full-text searching of the manuscript material.

Pish-posh, or the most important book of our century

Lindsay Gulliver

Perhaps no book of the mid-twentieth century would prove as divisive as Betty Friedan’s seminal 1963 tome, The Feminine Mystique. Invited to conduct a survey on the satisfaction of fellow female graduates at a college reunion, Friedan began an intent investigation into ‘the problem that has no name’, that is, a growing malaise amongst women who were seemingly living the American Dream. Credited with sparking the “second wave” of American feminism, the book – and Friedan herself – would serve as a flashpoint in social history, while also proving a publishing phenomenon.

The Papers of Betty Friedan, digitised from the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, offer an exciting glimpse into the writer’s world. Original surveys conducted with female graduates at colleges, including Smith, serve as raw data for Friedan’s arguments. Containing sensitive and private information on the lives of hundreds of women, great care has been taken to redact items within the collection in-keeping with archive standards. Nevertheless, honest answers on education, sex, work and marriage offer a deeply personal insight into women’s minds in the 1960s. Drafts of Friedan’s articles shed light on her progress, while correspondence demonstrates the reception her work received; two letter collections effectively showcase the extremes of popular opinion at the time.

Historical hate mail runs the gamut from amusing to cruel in a series of letters directed to Friedan after the publication of “The fraud of femininity”, an article in which she provocatively compared the suburban home to a concentration camp. Wrote one reader: ‘If American women are really as miserable as she says, maybe Russia should go ahead and drop the bomb and let us start all over’. Another would dismiss the eloquent article as ‘Pish-posh, Balderdash and hog-wash!’ Attacks often turned personal: ‘After reading this article I couldn’t help but picture Betty Friedan as selfish, cold, emotionless, and incapable of love.’

At the other end of the spectrum, many women considered The Feminine Mystique to be a life-changing account. In original reader letters: "good letters", one woman penned the following: ‘Thank you for your book, Mrs. Freidan. I consider it a social landmark […] because of your hard work and commitment, many of our daughters and sons will live richer and fuller lives and make their contributions to a world so desperately in need of dedicated people.’ Another highlighted the individual impact of the book, exclaiming that it ‘pinpointed my feeling of lack of identity and gives me courage’.

Though not universally popular, Friedan’s writings would become a battleground for gender politics over the coming decades, as one prescient correspondent surmised: ‘I just finished reading your book […] and I am convinced that it is the most important book of our century.’

“The way of progress was neither swift nor easy”: Taking a closer look at the legacy left by Marie Curie in material sourced from Bryn Mawr College

Rebecca Baxter

The Suffrage Ephemera and Martha Carey Thomas collections included in Gender: Identity and Social Change are made up of an array of correspondence, speeches and reports, many of which relate to the efforts of women to advance the status of women, women’s rights and female education in the early nineteenth century. Whilst these collections include letters shared amongst some of the most prominent women's rights activists and suffragettes such as Carrie Chapman Catt, Anna Howard Shaw and Emmeline Pankhurst, they also contain lesser-known works which highlight the challenges and disadvantages women of the period were struggling to overcome in their private and professional lives.

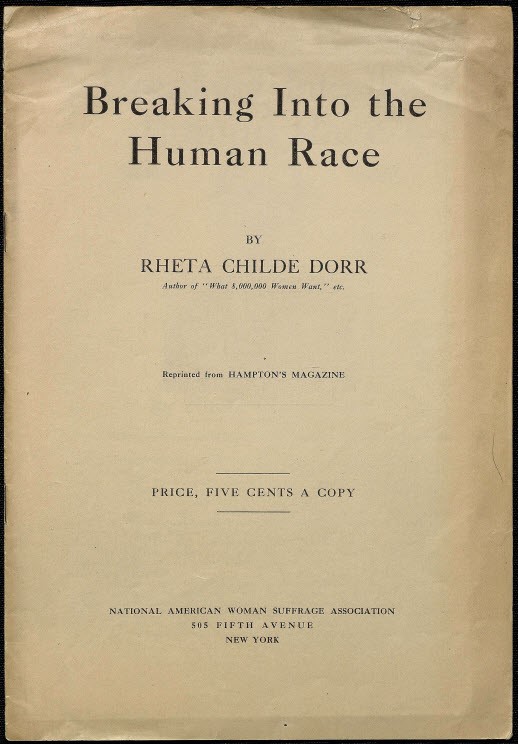

A particular favourite of mine is Rheta Childe Dorr’s 1912 pamphlet “Breaking Into the Human Race”. This work strove to dismantle the dominating public view of her time that “Women, being a sex, are expected to conform to a type, and they are admired and respected in proportion to their ability to conform”. Although Dorr refers to various women in the public eye to exemplify her point, her account of Marie Curie’s struggle to gain her scientific education forms the foundation of her argument.

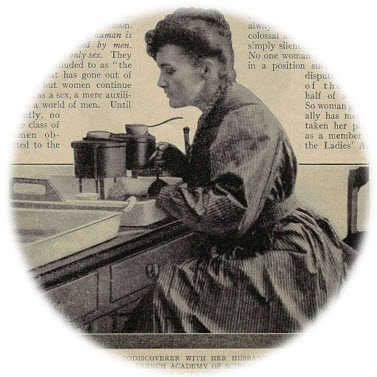

Dorr documents the various instances of gender discrimination Curie faced in her lifetime; her attempts to gain admittance to a university education, for example, proved one of the most trying periods of Curie’s life. “After a long persistence”, Dorr narrates, “the doors of the great laboratory were opened grudgingly to her”. Getting past the doors did not put an end to gender discrimination Curie suffered however. The French Academy, Department of Science for instance later admitted that Curie “was the foremost scientist in France … but as a candidate for the French Academy she did not even exist”. The reason for this: “it was possible for scientists to listen to a woman lecture on radio-activity. It was impossible for them to associate her with their after discussions of it.”

Curie fought on regardless, resiliently rebuffing the French Academy by means of both her pen and practice of chemistry. The French Academy were adamant that “A woman, whatever her intellectual qualifications, can no more become a member of an academy than the educated monkeys Consul […] for the same reason. Neither is Human”. Curie challenged the convention that “The rights of being human is entirely monopolised by men”, winning the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1911. Until her death in 1934 Marie Curie continued to push the boundaries of both science and women’s status and to this day remains the only woman to have been awarded the Nobel Prize twice.

Documents like Dorr’s pamphlet included in Gender: Identity and Social Change go beyond simply recording the “historic disadvantage women of genius and talent born with aptitude for scientific research, but were crushed by their unfavourable environment” (Martha Carey Thomas). Instead, they capture the various ways in which numerous women strove to deconstruct gender stereotypes and prejudices to realise their shared goal of ensuring “the girls of the next generation are given favourable conditions for this higher kind of scholarly development”.